|

Whitman’s New York

|

|

|

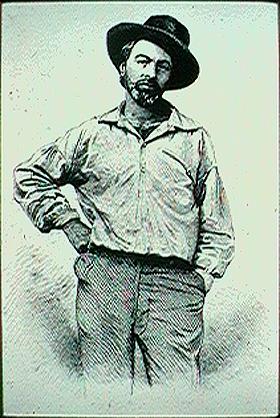

Arguably America’s greatest poet, Whitman held many of his fellow Transcendentalists’ beliefs. He championed the common man while simultaneously celebrating the interconnectedness of all living beings. Though heavily influenced by the natural world, he nonetheless relished the vibrancy of the city. Travel through the links below on a journey that chronicles the New York of Whitman’s life. |

|

Walt Whitman on Long Island

|

|

Walt Whitman in Brooklyn

|

|

|

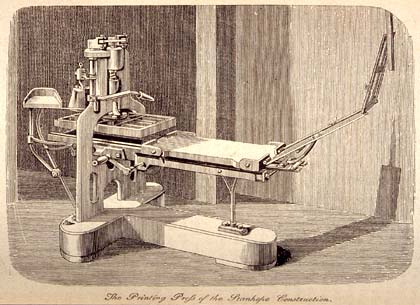

After a brief stint in New York City, Whitman returned to Long Island, where he founded one weekly newspaper and worked on another. He taught sporadically during this period as well. Left: At Bowne Printers, a reconstructed print shop and stationery store featured as part of the South Street Seaport Museum in Manhattan, Deidre Schaefer (right) learns to print using the same type of press Whitman would have used (photo by Linda Tate). |

|

|

During the next twenty years, Whitman moved back and forth between Brooklyn and Manhattan. He worked for a number of publications during these years. Left: Our group in front of the former offices of the Brooklyn Eagle. Pictured (left to right): Sarah Alouf, Cat Hall, Dr. Linda Tate, Anna Hughes, Deidre Schaefer, Dr. Patricia Dwyer, Dan Marrs, Lizzie Lowe (photo by Karen Karbiener). |

|

Walt Whitman on the Brooklyn Ferry

|

|

|

|

|

Learn

about the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, which rendered the

Catharine Slip Ferry (Whitman’s Brooklyn Ferry) obsolete by 1912. Though

Whitman’s ferry is no longer in use, learn about other ferry options. Visit

the Walt Whitman Park in Brooklyn. Left: Brooklyn Bridge Park, featuring the words from "Crossing Brooklyn Ferry" (pictured here: "and women generations," photo by Linda Tate).

|

|

|

|

|

Walt Whitman in Words

|

|

|||||

|

Whitman's Love of America

This page was created by Deidre Schaefer, an English major at Shepherd College. “American Transcendentalism: An Online Travel Guide” was produced by students in ENGL 446, American Transcendentalism, and ENGL 447, American Literature and the Prominence of Place: A Travel Practicum. These courses were team-taught in the Department of English at Shepherd College (now Shepherd University), Shepherdstown, West Virginia, in Spring 2002 by Dr. Patricia Dwyer and Dr. Linda Tate. For more information on the course and the web project, visit “About This Site.” © 2003 Linda Tate. |